Polymorphic linguistic renderings of fuzzy-scale conceptual measurement values: Mandarin "下 (xià)" vs. Spanish "poco"

Scale-values with wordings such as "more" and "less" are qualified as "fuzzy" because of the uncertainty of their range. These wordings occur within a fuzzy linguistic scale, namely a sequence of language-driven descriptors identified with fuzzy intervals, as could be "low" and "high" in English (e.g., the first of them spanning over 1 to 6, the second, over 4 to10 on a numerical scale comprising ten degrees). We here use small capitals (i.e., low, high) when language-independent conceptual values are meant, thus suggesting that such scale types, despite language-specific wordings of their values and possibly distinct segmentation according to culture, are cognitive in nature.

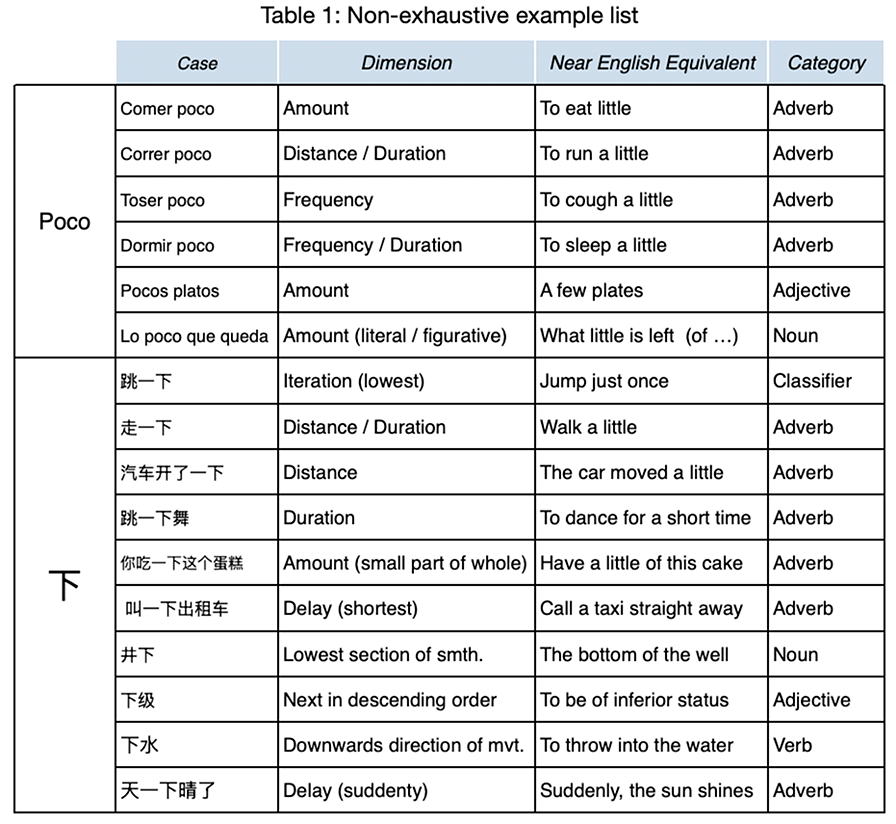

The values low and high identify scale regions applicable to diverse measurement domains, hereafter termed "dimensions" (quantity, as in "eat a little or much", pace, as in "running slowly or fast", rhythm, as in "beating slowly or fast", duration, as in "reading for a short or long time", distance, as in "living near or far away", frequency, as in "travelling rarely or often", etc.). These examples of process quantification show how the same values (low, high) materialise linguistically when ascribed to different dimensions (quantity, pace, distance, etc.). Both Mandarin "下 (xià)" and Spanish "poco" neutralise the dimensional reference of the low value pointed out above, in that they consistently denote a fuzzy segment on the feeblest magnitude zone of the dimension scale to which they apply.

Both quantifiers suit several dimensions depending on context: "poco" can stand for duration, quantity, distance and frequency, The dimensional scope of "下" is slightly different: besides the three first foregoing ones, it can stand for delay (the immediacy of an action to be undertaken, the suddenty of an event), position (the following member of a descending-ordered sequence, the bottom or the lowest section of something, a beneath-placed entity). Polysemy occurs when either "poco" or "下" can, in the same context, refer to more than one dimension (duration / frequency, duration / distance, etc.). "下" exhibits a higher versatility in terms of word category: as "poco" it can act as an adverb, an adjective and a noun, but also as a classifier or a verb identifying a downwards movement direction. Yet, whatever their grammatical form, both consistently implement the same inferior fuzzy-scale value segment.

The conceptual relatedness of low as a position to less as a magnitude (and of its converse high to more) is at the core of the verticality Image Schema fathered by Mark Johnson and George Lakoff in 1987. Metaphors based on the vertical axis ("moral uprightness", "standalone app", "head of staff", "to land in the gutter", "to feel down" etc.) appear to rely on the high/low contrast. We here address the rôle of the verticality Image Schema in quantification, focusing on how low materialises linguistically in the context of different dimensions.

Polymorphism is here meant as the combination of multi-dimensional compatibility, polysemy and cross-categorial identity of lexemes expressing the same fuzzy-scale value. We intend to stress the conceptual nature of fuzzy-scale value ranges imposed onto the various dimensions over which quantification takes place. Our focus on low is meant to highlight the comparison between near-equivalent quantifiers instantiating one and the same segment of a generic fuzzy measurement scale in different languages (here, Mandarin and Spanish), so as to include degrees of polymorphism in the list of factors that define linguistic complexity. However, if considering cognitive load in language processing, polymorphism increases language complexity (calling for higher context-driven disambiguation efforts), taking "compactness" as a a measuring scale, (following Kolmogorov's compression criterion), could rate highly polymorphic languages as "simpler". Complexity of use thus differs from complexity of structure.

References

Akay, D., Duran, B., Duran, E., Henson, B. & Boran, F. (2021). Developing a labeled affective magnitude scale and fuzzy linguistic scale for tactile feeling. Human factors and ergonomics in manufacturing & service industries, 31 (1), 13-26. https://doi.org/10.1002/hfm.20866

Fernández Leborans, M. & Sánchez López, C. (2011). Las interpretaciones de “mucho” (y cuantificadores afines). In M. Escandell, M. Leonetti & C. Sánchez López (Eds.), 60 problemas de gramática dedicados a Ignacio Bosque (pp. 77-82). Madrid: Akal, 77-82.

Gibbs, R. Beitel, D., Harrington, M., & Sanders, P. (1994). Taking a stand on the meaning of Stand: Bodily experience as motivation for polysemy. Journal of Semantics, 11 (4), 231–251. https://doi.org/10.1093/jos/11.4.231

Gil, M., De la Rosa de Saa, S. & Sinova, B (2015). Analyzing data from a fuzzy rating scale-based questionnaire. A case study. Psicothema 27(2), 182-191. https://doi.org/10.7334/psicothema2014.268

Grünwald, P. D. (2007). The Minimum Description Length Principle. Cambridge, Mass : MIT Press.

Lamarre, Ch. (2008). The linguistic categorization of deictic direction in Chinese – with reference to Japanese. In D. Xu (Ed.), Space in Languages of China (pp. 69-97). Dordrecht: Springer, 69-97.

Real Academia Española y Asociación de Academias de la Lengua Española (2009-2011). Nueva Gramática de la Lengua Española. https://www.rae.es/gramática/

Wachowiak, L, Gromann, D & Xu, Ch. (2023). The Image Schema VERTICALITY: Definitions and annotation guidelines. In M. Hedblom & O. Kutz (Eds.), Proceedings of The Seventh Image Schema Day (ISD7), September 2023, Rhodes, Greece. Vol. 3511. Aachen: CEUR Workshop Proceedings.