Grammaticalization Pathways of Progressive Aspect in Korean and Hindi: A Cross-Linguistic Perspective

Introduction: Progressive aspect markers commonly arise through processes involving grammatical reanalysis and typological shifts. This study investigates the grammaticalization pathways of progressive aspect markers in Korean and Hindi, exploring their historical developments despite genealogical differences. Both languages derive progressive markers primarily from imperfective constructions, adding complexity to Bybee et al.'s (1994) model, which predominantly links progressive markers to locative or posture verbs. Rather than contradicting, these findings enrich Bybee's typology by highlighting alternative grammaticalization sources.

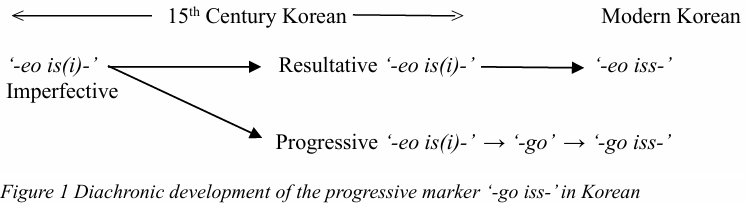

Historical Development in Korean: In Middle Korean (15th century), the construction -eo iss- carried both resultative and progressive meanings (Kim 2003, 2009; Park 2011). With the expansion of the connective -go from the 15th to the 17th century, the -go is(i)-[1] construction began selectively replacing -eo is(i)- based on verb transitivity. Over time, the -go iss- construction emerged predominantly as a progressive marker with transitive verbs, while -eo iss- specialized in conveying resultative meaning. This transition exemplifies grammatical specialization in progress but retains some polysemy, reflecting the early stages of specialization as described by Hopper (1991). Below, Figure 1 schematically represents this historical development, followed by illustrative examples from Middle and Modern Korean.

Examples from Middle Korean clearly demonstrate this original polysemy (Kim 2009: 183):

(1) a. Jin-e bo-m-al nalawad-a seoleu gideuly-eo isi-ni… [Yeongga 1464, 1:78b]

truth-LOC see-NOMZ-ACC raise-CON together wait-eo isi-CON

‘To obtain the ability to see truth, (they) stayed waiting together…’

b. Seonhye nib-eo is-deo-si-n nogbi os-al bas-a…

Seonhye put.on-eo is-RETRO-HON-REL deer.skin clothes-ACC take.off-CON

'Seonhye took off the deer skin clothes that he was wearing and…’ [Wolinseogbo 1459, 1:15b]

Modern Korean reflects the specialized meanings clearly distinguished:

(2) a. geu-neun s-eo iss-da. (‘He is standing.’)

He-TOP stand-CONN be-DECL

b. geu-neun gadili-go iss-da. (‘He is waiting.’)

He-TOP wait-CONN be-DECL

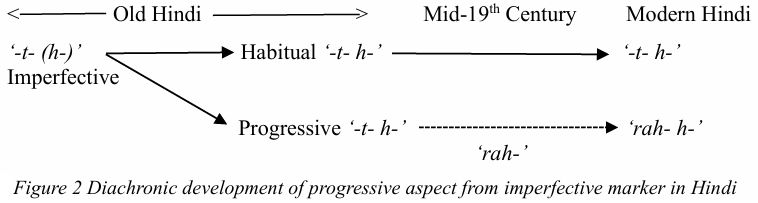

Historical Development in Hindi: In Classical Hindi, the -t- h- construction exhibited ambiguity, marking both habitual and progressive readings (Kellogg 1893; Montaut 2006).[2] The introduction and rise of rah- h- in Middle Indo-Aryan (Deo, 2006) resulted in a clearer functional specialization in Modern Hindi, distinctly separating habitual (-t- h-) from progressive (rah- h-) aspects (Hackman 1976; Montaut 2006). This clear differentiation aligns closely with Hopper's specialization criterion, showcasing a relatively advanced stage of grammaticalization compared to Korean. Below, Figure 2 schematically represents this historical development, followed by illustrative examples from Old and Modern Hindi.

As Montaut (2006: 6) notes, in the 19th century, the modern contrast between habitual/generic and progressive was still not well established. The shorter form (-t- h-) was glossed with both present meanings in Kellogg (1893), whereas the longer periphrastic form (rah hai, lit. ‘is stayed’) was glossed with a more expressive meaning such as “be engaged in.” The following examples (3a~b) are cited from Montaut (2006: 6):

(3) a. ve khel-t-e hain. (‘They play’ / ‘They are playing’)

they play-IMPERF-M.PL be.PRES.3.PL

b. ve khel rah-e hain. (‘They are engaged in playing’)

they play stay-PERF-M.PL be.PRES.3.PL

Modern Hindi reflects the specialized aspectual distinction that emerged through grammaticalization:

(4) a. ve khel-t-e hain. (‘They play’)

they play-IMPERF-M.PL be.PRES.3.PL

b. ve khel rah-e hain. (‘They are playing’)

they play PROG-M.PL be.PRES.3.PL

Discussion and Conclusion: The grammaticalization pathways of progressive markers in Korean and Hindi illustrate both shared typological patterns and notable language-specific differences. Employing Hopper’s (1991) criteria of specialization and Lehmann’s (2002 [1982]) grammaticalization parameters provides clearer insight into the diachronic trajectories of these markers. While Hindi exhibits advanced functional specialization, Korean remains in an intermediate stage, retaining polysemy. This cross-linguistic examination thus contributes to a nuanced understanding of grammaticalization processes, revealing the intricate interplay between universal tendencies and language-specific grammatical evolution.

[1] -is(i)- is the old Korean form that later developed into iss- in Modern Korean.

[2] ‘h-’ refers to the auxiliary verb honā (‘to be’), which appears in inflected forms (e.g., hun, hai, hain, thā) to mark tense in aspectual constructions.

References

Bybee, J. L., Perkins, R. D., & Pagliuca, W. (1994). The evolution of grammar: Tense, aspect, and modality in the languages of the world (Vol. 196). Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Deo, A. (2006). Tense and aspect in Indo-Aryan languages: variation and diachrony (Doctoral dissertation, Stanford University).

Hackman, G. J. (1976). An Integrated Analysis Of The Hindi Tense And Aspect System. University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign.

Hopper, P. J. (1991). On some principles of grammaticization. Approaches to grammaticalization, 1, 17-35.

Kellogg, S. H. (1893). A Grammar of the Hindí Language: In which are Treated the High Hindí, Braj, and the Eastern Hindí of the Rámáyan of Tulsí Dás: Also the Colloquial Dialects of Rájputáná, Kumáon, Avadh, Ríwá, Bhojpúr, Magadha, Maithila, Etc.: with Copious Philological Notes. Kegan Paul, Trench, Trübner.

Kim, M. (2009). The intersection of the perfective and imperfective domains: a corpus-based study of the grammaticalization of Korean aspectual markers. Studies in Language. International Journal sponsored by the Foundation “Foundations of Language”, 33(1), 175-214.

Kim, M. (2003). Discourse, Frequency, and the Emergence of Grammar: A corpus-based study of the grammaticalization of the Korean existential verb is (i)-ta. University of California, Los Angeles.

Kumar, B. (2025). An Overview of Grammaticalization in the Korean Aspectual System. Acta Linguistica Asiatica, 15, 1.

Lehmann, Christian. (2002). Thoughts on Grammaticalization (2nd ed.). Erfurt: Seminar für Sprachwissenschaft der Universität.

Montaut, A. (2006). The evolution of the tense-aspect system in Hindi/Urdu. In Proceedings of LFG Conference 2006 (p. prépublication). en ligne (CSLI publications).

Nam, S. (2012, June 7–8). Durative aspect and pragmatics of ‘-e iss-’ and ‘-ko iss-’ in Korean [Conference presentation]. Workshop on Tense and Aspect in Korean and Japanese, Seoul, South Korea.

Nam, S. (2010). Some issues regarding the durative constructions ‘-ko iss-’ and ‘-e iss-’ in Korean. Seoul: Korean Society for Language and Information.

Park, J. (2011). Tense, Aspect, Modality. Korean Linguistics, 60, 289-322.