Fixed in English, not (that) free in Slovak: Two cross-linguistic case studies on word order

Slovak is generally claimed to have a very flexible word order. In fact, it has been noted that “[m]odern Slovak sources decline to refer to any unmarked order of constituents in terms of basic word order” (Short 2002: 566). This is confirmed by a review of grammars (e.g. Pauliny et al. 1963; Orlovský 1971; Mistrík 1983, 1988, 2003; Pauliny 1981, 1997; Pavlovič 2012; Ivanová 2016) and linguistic journals such as Jazykovedný časopis and Slovenská reč, which only discuss information structure as a factor. However, Hawkins’ (1994) Performance-Grammar Correspondence Hypothesis (PGCH) predicts that, due to processing efficiency, the restrictive word orders of languages such as English will be mirrored as preferred in languages that are more flexible, such as Slovak. In other words, according to PGCH, Slovak should also exhibit a preference for certain word orders, implying the existence of unmarked orders. I present two studies in support of PGCH, providing evidence for preferred/unmarked syntactic patterns in Slovak.

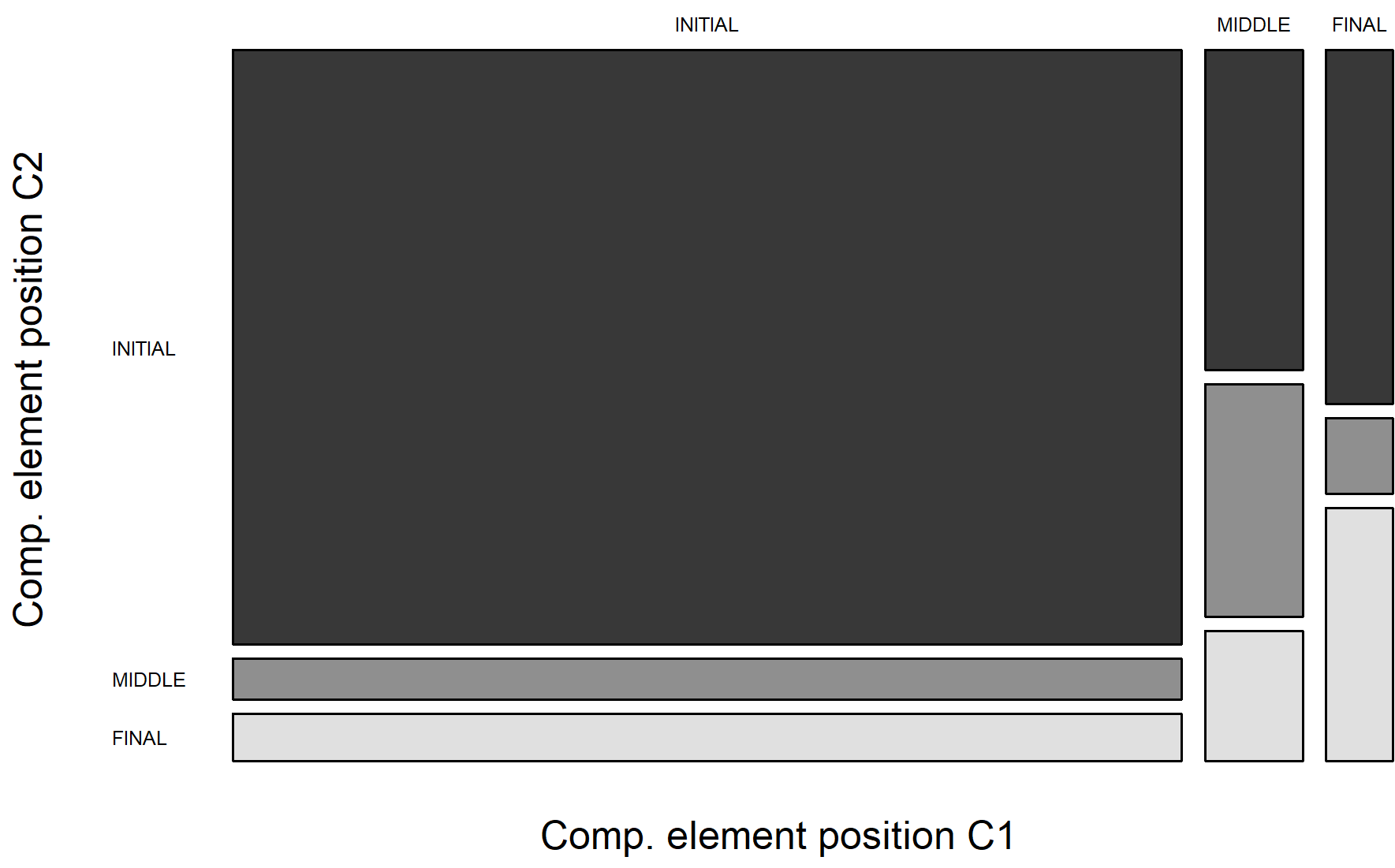

First, an investigation of the comparative correlative (CC) based on 899 tokens from the Slovak Web 2011 corpus. The CC consists of two subclauses C1 and C2 ([Čím menej rečí tu bude,]C1 [tým skôr zaspím]C2 ‘The less talking there is here, the sooner I will fall asleep’), each comprising a fixed clause-initial element čímC1/týmC2, an obligatory comparative element (menej ‘less’/ skôr ‘sooner’) and an optional clause slot (cf. Horsch 2021: 198). I focus on the comparative element, which can be placed in Initial (Čím viac rokov učím […] ‘The more years I teach’), Middle (Čím je viac dusno […] ‘The stuffier it is’), and Final (Čím sme boli bližšie […] ‘The closer we were’) positions. Despite this flexibility, the corpus data reveal a clear preference, in both subclauses, that mirrors the order which is fixed in English, i.e., with the comparative element immediately following the clause-initial element (cf. Culicover and Jackendoff 1999: 567) (Figure 1 and Table 1). A Pearson’s chi-squared test shows that this preference is statistically significant (χ2 = 139.68, df = 4, p <0.001***).

Second, I present acceptability judgments obtained using the magnitude estimation method (Hoffmann 2013) from 39 L1 Slovak speakers. This study investigates syntactic patterns with postverbal NP and PP (e.g. Ján [VP[dal] NP[knihu ] PP[na stôl ]] ‘John put a book on the table’). Due to processing efficiency (weight effects), [VP NP PP] is the “basic” and “grammaticalized” order in English (Hawkins 1994: 20), although speakers may shift the NP when it is considerably lighter than the PP, resulting in [VP PP NP] (Hawkins 1994: 57). I tested the variables Weight Order (levels: Heavy-Light; Light-Heavy) and Phrase Order (levels: NP-PP; PP-NP) and their interactions. My results (Fig. 2 and Tab. 2), corroborated by mixed-effects modelling, reveal weight effects (Light-Heavy is always preferred, p<0.001***) and that NP-PP was clearly preferred over PP-NP (p=0.042*), suggesting that the NP-PP order also plays a role in Slovak. The case studies show that there are factors beyond information structure that influence word order and the existence of unmarked/basic word orders in Slovak.

| C1 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Initial | Middle | Final | Totals | ||

| C2 | Initial | 667 | 46 | 53 | 766 |

| Middle | 37 | 27 | 15 | 79 | |

| Final | 28 | 6 | 20 | 54 | |

| Totals | 732 | 79 | 88 | 899 | |

| Table 1: Comparative Element Position across C1 and C2, Slovak Web 2011 |

| Weight Order | Phrase Order | z-score | SD | SE |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Light_Heavy | NP_PP | 0.428 | 0.770 | 0.093 |

| Heavy_Light | NP_PP | –0.148 | 0.756 | 0.091 |

| Light_Heavy | PP_NP | 0.173 | 0.748 | 0.090 |

| Heavy_Light | PP_NP | –0.333 | 0.724 | 0.088 |

| Table 2: Z-score means of Weight Order:Phrase Order (n=39) |

References

Hawkins, J. A. (1994). A performance theory of order and constituency. Cambridge UP.

Hoffmann, T. (2013). Obtaining introspective acceptability judgements. In M. Krug & J. Schlüter (Eds.), Research Methods in Language Variation and Change (pp. 99–118). Cambridge UP.

Horsch, J. (2021). Slovak Comparative Correlatives: A Usage-based Construction Grammar Account. Constructions and Frames, 13(2), 193–229.

Ivanová, M. (2016). Syntax slovenského jazyka (Second edition). Vydav. Prešovskej Univerzity. http://www.pulib.sk/web/kniznica/elpub/dokument/Ivanova4

Mistrík, J. (1983). Moderná Slovenčina. Slovenské Pedagogické Nakladateľstvo.

Mistrík, J. (1988). A Grammar of Contemporary Slovak. Slovenské Pedagogické Nakladateľstvo.

Mistrík, J. (2003). Gramatika Slovenčiny. Slovenské Pedagogické Nakladateľstvo.

Orlovský, J. (1971). Slovenská syntax [Slovak syntax]. Obzor.

Pauliny, E. (1981). Slovenská Gramatika (Opis jazykového systému). Slovenské Pedagogické Nakladateľstvo [Slovak Pedagogical Press].

Pauliny, E. (1997). Krátka Gramatika Slovenská [A brief grammar of Slovak]. Národné literárne centrum - Dom slovenskej literatúry [National Litereary Center - House of Slovak Literature].

Pauliny, E., Ružička, J., & Štolc, J. (1963). Slovenská Gramatika [Slovak Grammar]. Slovenské Pedagogické Nakladateľstvo [Slovak Pedagogical Press].

Pavlovič, J. (2012). Syntax Slovenského Jazyka I. http://pdf.truni.sk/e-ucebnice/pavlovic/syntax-1.

Short, D. (2002). Slovak. In B. Comrie & G. G. Corbett (Eds.), The Slavonic Languages (pp. 533–592). Routledge.