Case variation in Ukrainian direct addresses in a bilingual context

In Modern Ukrainian, addresses use either the vocative or nominative case. Since 1991, only the variant with the vocative case has been approved as a standard one for nouns of masculine and feminine gender in the singular, with some exceptions described in grammar (Ukraïns′kyj pravopys 1993); the Soviet-era norm allowed for variations (Ukraïns′kyj pravopys 1960). The use of the vocative case in addresses is cultivated and maintained as an authentic feature of the Ukrainian language that distinguishes it from Russian. Since the 1920s and up to the present day, linguists have associated the spread of the use of the nominative case in addresses with the undesirable influence of the Russian language on the grammatical structure of Ukrainian (Yasakova, et al. 2022: 7-8).

If the use of nominative were due to the Russian influence, then it would fall under the category of pattern-borrowing, a phenomenon where “the patterns of distribution, of grammatical and semantic meaning, and of formal-syntactic arrangement ... are modeled on an external source” (Matras, Sakel: 829-830). Our ongoing research into case variation in Ukrainian address constructions, however, suggests that multiple factors likely drive this variation. These potential factors encompass frequency, grammatical and phonetic characteristics, pragmatics, and lexical compatibility (Shvedova, Lukashevskyi 2025). Still, cases can vary even under formally identical conditions, as demonstrated by the following examples from the parliamentary transcripts:

Djakuju, Adame (Voc) Ivanovyču (Voc).

Djakuju, Adame (Voc) Ivanovyč (Nom).

Djakuju, Adam (Nom) Ivanovyč (Nom)

'Thank you, Adam Ivanovich'

In this study, we aimed to trace the influence of speakers' Ukrainian-Russian bilingualism on their choice of vocative or nominative in Ukrainian speech. For the research, we chose 28,896 contexts with addresses in different cases from the parliamentary transcripts of 2007-2024, including texts by 276 speakers, at least 10 contexts from each. The contexts were selected from officially published parliamentary transcripts annotated with UDPipe2 using the uk_parlamint model. The model allowed us to distinguish the nominative in address from other functions of this case (Shvedova, et al. 2025). We analyzed the languages used by each speaker in the parliament and speakers’ origin regions and looked for a correlation between this and the use of vocative or nominative.

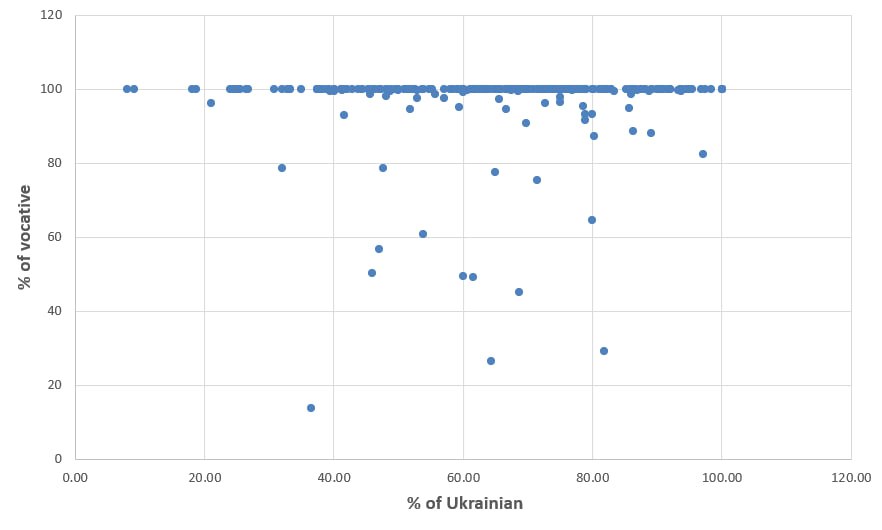

Fig. 1 shows speakers by their case choice (% of vocative in the horizontal direction) and language usage (% of Ukrainian in all speakers' transcripts in the vertical direction). Among those who switch to Russian, there are people with both low and high proportions of vocative case in their addresses. Switching to Russian in the parliament ceased after 2017; it was practiced mainly by representatives of pro-Russian political forces to demonstrate their agenda (Kanishcheva, et al. 2023). The use of the nominative case in the vocative function obviously does not carry such ideological significance; it is individual and varies both among those who switched to Russian and among those who speak only Ukrainian.

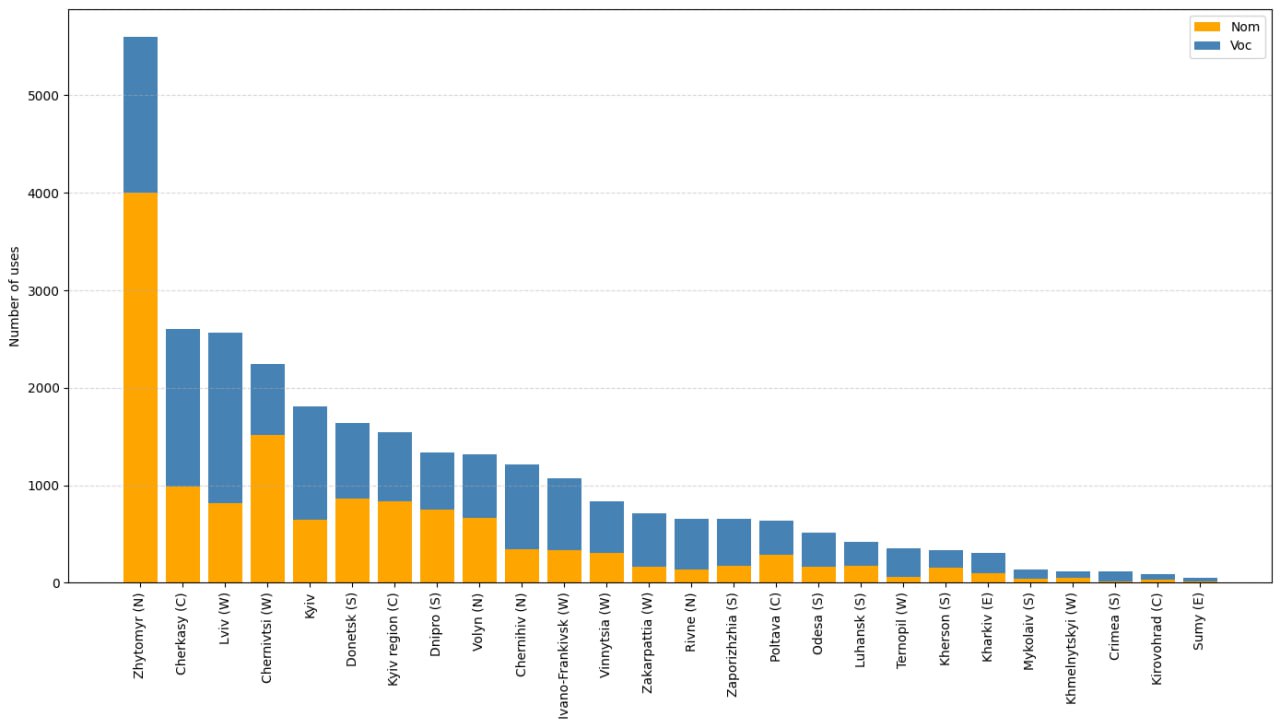

Fig. 2 shows the distribution of the data by region; the share of vocative in addresses has little correlation with the greater prevalence of Russian in the regions of the East (E) and South (S) (Ponad 50%… 2024). The individual choice of the speaker has a strong influence. For example, three MPs from Crimea, whose first language, according to their biographies, was Russian (Refat Chubarov, Lyudmyla Denisova, Iryna Friz), use the vocative in 83-98% of their addresses, which is above the average. On the other hand, there are MPs from the predominantly Ukrainian-speaking region of Lviv, who use vocative in their addresses in 25-40% of examples (Mykhailo Khmil, Rostyslav Shurma, Ivan Vasyunyk).

With such significant individual variation, the parliamentary corpus does not reveal regional patterns in case choice. Nor does it show a significant influence of Russian on this variation at the individual level. These data strongly suggest that Russian influence on case choice in Ukrainian direct addresses is unlikely.

Acknowledgment

This work received support from the CA21167 COST action UniDive, funded by COST (European Cooperation in Science and Technology).

References

Ukraïns′kyj pravopys. (1993). Kyiv (In Ukrainian)

Ukraïns′kyj pravopys. (1960). Kyiv (In Ukrainian)

Yasakova, N.Y., Kobchenko, N. V., & Ozhohan, V.M. (2022). Ukraїnsʹkyĭ vokatyv: Zmіna pohliadіv na funktsії morfolohіĭnoї formy na tli suspіlʹnykh transformatsіĭ. Studia z Filologii Polskiej i Słowiańskiej, 57, Article 2673. (In Ukrainian)

Matras, Y., Sakel, J. (2007): Investigating the mechanisms of pattern replication in language convergence. Studies in Language 31 (4), 829–865.

Shvedova, M., & Lukashevskyi, A. (2025). Case choice in Ukrainian vocative expressions: A study of parliamentary transcripts (1990–2024) annotated with Universal Dependencies. In Grammar and Corpora: 10th International Conference, 26–28 June 2025. Book of Abstracts (pp. 106–108). University of Latvia Press.

Shvedova, M., Lukashevskyi, A., & Rysin, A. (2025). Developing a Universal Dependencies Treebank for Ukrainian Parliamentary Speech. In Proceedings of the Fourth Ukrainian Natural Language Processing Workshop (UNLP 2025) (pp. 55–63). Association for Computational Linguistics.

Kanishcheva, O., Kovalova, T., Shvedova, M., & von Waldenfels, R. (2023). The Parliamentary Code-Switching Corpus: Bilingualism in the Ukrainian Parliament in the 1990s–2020s. In Proceedings of the Second Ukrainian Natural Language Processing Workshop (UNLP) (pp. 79–90). Association for Computational Linguistics.

Ponad 50% ukraïnciv spilkujut′sja vdoma til′ky ukraïns′koju movoju — opytuvannja [Over 50% of Ukrainians speak only Ukrainian at home - survey] (2024). Suspil′ne. (In Ukrainian) [Electronic resource]: https://suspilne.media/culture/721570-ponad-50-ukrainciv-spilkuutsa-vdoma-tilki-ukrainskou-movou-opituvanna/