Voice is not a spell-out domain: Ask Kurdish and Baxtiari

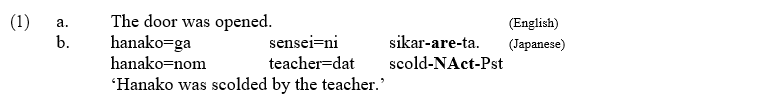

INTRODUCTION. Non-active voice (henceforth, NAct) structures refer to a group of remarkably similar structures which prevent external arguments from surfacing syntactically, such as anticausatives, dispositional middles, and passives. NAct structures are classified morphologically into two types in many languages: analytic NAct voice is expressed through a combination of an auxiliary and a non-finite element, as in English (1a), while synthetic voice is expressed by a designated NAct morpheme, as in Japanese (1b).

NAct voices can also surface syncretically across languages (e.g., Russian, Greek, Korean, etc.). That is, two or more underlyingly distinct NAct voices are pronounced identically.

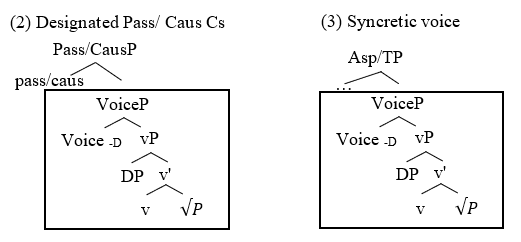

Oikonomou and Alexiadou (2022:25), make a generalization about voice syncretism in which they state that “voice syncretism is associated with synthetic morphology”. They argue that analytic NAct voice, unlike synthetic NAct voice, is associated with a single interpretation. Only synthetic morphology can be interpreted syncretically as passive, middle, or other voices. In their analysis, they take voiceP as a spell-out domain and relate syncretism and non-syncretism to the absence and presence of a designated head above voiceP, respectively. Thus, if a language aims to specify the NAct meaning, it requires additional heads and since these additional heads lie outside voiceP, they must be spelled out separately. Accordingly, this phase-external phrase has a designated interpretation. On the other hand, in the absence of a higher head, the vP and voiceP sequences remain in the same spell-out domain and are transferred to interfaces simultaneously, resulting in a synthetic NAct voice with a syncretic interpretation (3).

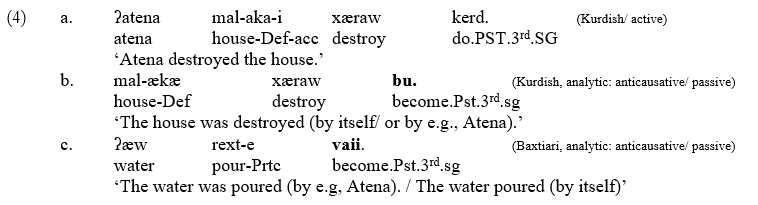

DATA. This generalization, however, is at odds with two related Iranian languages, namely Kurdish and Baxtiari:

In the active sentence (4a), with a complex predicate , the light verb kerden ‘to do’, combines with a predicative item, here, a noun. To form a NAct counterpart, Kurdish can, analytically, replace the active LV, kerden ‘to do’ with the NAct auxiliary, bun ‘to become’. This structure is syncretic, lending itself to two interpretations: it has either an anticausative reading, (i.e., the house destroyed by itself), or a passive reading, in which an implicit agent is present.

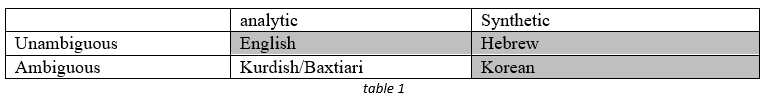

The data thus provide evidence that there is no constraint on combinations of syncretic readings and forms (i.e., synthetic or analytic) as is shown in table 1. The shaded cells were introduced by O&A.

We can conclude that whether a voice is unspecified or not does not reflect its analytic or synthetic nature. Therefore, both non-/syncretic synthetic and analytic NAct forms should be possible in principle, and whatever mechanism drives non-/syncretism differs from what is responsible for analytic/synthetic. We adopt O&A’s claim that the analytic form occurs when the derivation spells out voices separately. However, we argue against the idea that voiceP is a spell-out domain. Hence, if a particular head (Pass or Cause) appears, a synthetic form can still be generated. In addition, the head of VoiceP in languages can still be spelled out analytically without any specially designated interpretation. Concretely, we propose that NAct voices have the same underlying structure: VoiceP> PredP> RootP. It is language-specific properties, however, that determine whether voice, Pred, and Root heads are spelled out as one unit (i.e., synthetic) or separately (i.e., analytic).

References

Alexiadou, A. & E. Doron. (2012). The syntactic construction of two non-active voices: Passive and middle. Journal of linguistics 48 (1), 1–34

Oikonomou, D. & Alexiadou, A.( 2022). Voice Syncretism Crosslinguistically: The View from Minimalism. Philosophies, 7(1), 19.